Do we know is really happening when playing an RPG? One particularly thorny part is figuring out who is actually speaking at any one moment. This blog tries to think about this using a bit of literary theory.

In this text-world, the speaker is given as 'I'. This person is obviously not acting within the player-world (as they would be if they said 'I'm just going to mute myself for a second'). Therefore, the 'I' is not Sean McCoy themselves. It must be Gizzard [I know this is laboured, but this is what literary analysis is like]. This is not direct speech by Gizzard as Sean McCoy tends to use a voice in the video when he is doing direct speech. Therefore we can say it is an act of narration by Gizzard of what they are doing.

The narrator remains saying 'I' but it is clearly no longer Narrator-Gizzard remarking on what Gizzard is doing. The only logical alternative is that this is Sean McCoy talking. However, just as we had the creation of a Narrator-Gizzard we also have one for Sean McCoy. This is not the real player-world Sean McCoy remarking on something in the player-world but one that is functioning within the text-world/game-world (2). This is the faded head above: Narrator-Sean.

Here we are still first-person but now it is 'us' and 'we'; returning us to the perspective of Gizzard (or, Narrator-Gizzard) themselves as they consider the use of the armour for the characters within the game-world/text-world.

In this model, the false-player-verifiable world has been renamed as the narrator-world. The narrators within it can be closer to the player or the game-world and will move around an awful lot in any session.

Yeah, you aren’t proficient with glaives, unfortunately.

This is a quote from a bit of Critical Role where the GM is telling a player that they can't use an item. In this quote, who is speaking and being spoken to?

If the 'you' is the player (Laura Bailey), it makes little sense why Matthew Mercer would be telling her she can't use glaives. Is the 'you' the character Jester? It seems unlikely given that Matthew Mercer is talking as himself to a fictional character sitting at the table who doesn't know themselves if they can use a glaive well.

These may seem like flippant questions which we can intuitively answer, even if that might be hard to articulate. However, I think that trying to articulate an answer helps us to reflect on RPGs. In particular, I think it might help us to consider approaches to defining differences between "types" or "styles" of play.

In order to attempt this I am going to be applying some Text-World theory (overviewed in this post) to a short extract from an Into the Odd recording. You don't need to have read that post to follow this one. I am going to edit some of the theory's jargon to make it more appropriate to RPGs. Where I do this I will put a footnote (x) to the actual term. This is still quite a dense blog, so please scroll to the conclusion if you want my main points.

Let's get started. The extract we are looking at is from this video of Chris McDowall running a little bit of the game for Sean McCoy and Alan Gerding:

So I’m gonna go, try get the armour down from the wall, try check it out. I think Gizzard is picturing that this is rich, noble armour, definitely would protect us for now, and if not would fetch a pretty penny on the black market when we get out.

The speaker is Sean McCoy, and their character is Gizzard. Let's start figuring out the levels of narration following Text-world theory.

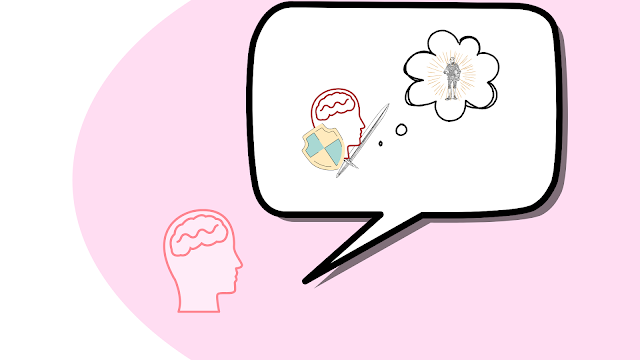

Our first level is the player-world(1): this is the "real" world where the conversation is happening. It includes the three speakers (the three heads in the image above) as well as the implied audience of the YouTube video (the faded person at the bottom).

From here we move into their speech, called the 'text-world' in text-world theory. Our first one is associated with the first sentence: So I'm gonna go, try get the armour down from the wall, try check it out.

In the picture above we can see a faded Gizzard (with sword and shield). Text-world theory posits that narrators exist as implied characters in the text-world, even when the narrator is narrating their own actions. Therefore we have two "characters": Gizzard and Narrator-Gizzard.

After this sentence the narrator switches and with that we create a new text-world: I think Gizzard is picturing that this is rich, noble armour, definitely would protect...

The narrator remains saying 'I' but it is clearly no longer Narrator-Gizzard remarking on what Gizzard is doing. The only logical alternative is that this is Sean McCoy talking. However, just as we had the creation of a Narrator-Gizzard we also have one for Sean McCoy. This is not the real player-world Sean McCoy remarking on something in the player-world but one that is functioning within the text-world/game-world (2). This is the faded head above: Narrator-Sean.

This sentence though includes another world-switch: ...definitely would protect us for now, and if not would fetch a pretty penny on the black market when we get out.

Here we are still first-person but now it is 'us' and 'we'; returning us to the perspective of Gizzard (or, Narrator-Gizzard) themselves as they consider the use of the armour for the characters within the game-world/text-world.

To summarise the journey of Sean-McCoy's voice in this one small section I have this:

Sean McCoy from the player-world speaks. He first speaks as Narrator-Gizzard, narrating what Gizzard does in the game-world/text-world. We then switch to Narrator-Sean who gives his perspective of Gizzard's thought processes and in the process of that the narration of Narrator-Gizzard re-emerges. This is happening very smoothly and with almost no cognitive effort.

You might wonder why I have put Narrator-Sean closer to the player-world Sean (in the grey circle at the top left). The reason is to do with an interesting feature of text-worlds: they can be described as 'player-verifiable' (3) or 'character-verifiable' (4).

If we look back at the two sentences that Narrator-Gizzard speaks: 'So I'm gonna go, try get the armour down from the wall, try check it out.... definitely would protect us for now, and if not would fetch a pretty penny on the black market when we get out'. Both of these sentences have information that could only every be "accessed" by people in the game-world itself. There is no actual player-world way to check, argue against or validate that information. This is in contrast to the player-verifiable sentence we had earlier: 'I'm just going to mute myself.' There, the players can look at the real world and check if the speaker does do this/if they are able to and so forth. It is the difference between me writing 'It is raining where you live' and 'it is raining where Hafnar Iron-Fist lives'. One of those you can check for yourself, the second only Hafnar Iron-Fist knows.

Now, when we look at the sentence by Narrator-Sean: I think Gizzard is picturing that this is... We seem to see something slightly different. This is partly still a character-verifiable world, the only people who could know what Gizzard is picturing is Gizzard themselves or a mind-reader in the game-world. However, here it feels more like we (in the player-world) could verify this information. The 'I think' is almost an invitation to be interrupted, the language of "story-games" often seems to use these kinds of statements more, for example.

This is something that text-world theory says happens in narratives/literature. That where there is a narrator who is talking about character-verifiable worlds or sharing their internal perspectives and inner thoughts, we in fact perceive them as player-verifiable worlds. This is still true to an extent to the Narrator-Gizzard as well, but I think it is stronger (and this matches with text-world theory's findings) when it is coming from Narrator-Sean and from third person narration.

I think this kind of false-player-verifiable world (5) is readily observed in RPGs. It ties in to ideas around the relationship of a printed adventure/character sheet/mechanics to the game-world. With these player-world elements, even though the game-world is a fictional space that only the characters belong to, it becomes perceived as player-verifiable throughout.

To some extent I think that one could argue that the character-verifiable game-worlds become so player-verifiable that the characters are actually almost pushed out. For me, this is seen the classic of people looking at a character sheet to see what their character can do.

The starting quote from the DnD 5e game is an example of these false-player-verifiable worlds: Yeah, you aren’t proficient with glaives, unfortunately.

This conversation is ultimately about a character deep in the game-world. It is determining information that is really character-verifiable and not player-verifiable. However, in the false-player-verifiable worlds of narrative, it becomes player-verifiable. Very literally, the GM is able to look at something (a character sheet) that exists in the player-world and use that information to verify the truth of the fictional game-world of the characters. Here the player-world, is penetrating, almost overriding the game-world.

Let's see if I can now answer my initial question about who is speaking. Who is 'you'? The GM is not talking to the player, Laura. Nor is he talking to the character Jester. Instead I feel that he is talking to an amalgamation of Narrator-Laura and Narrator-Jester. This figure is someone who is able to transmit and carry meaning between the player-world and the game-world.

To bring this back to our original images, I have got to something like this:

In this model, the false-player-verifiable world has been renamed as the narrator-world. The narrators within it can be closer to the player or the game-world and will move around an awful lot in any session.

This leads me to my conclusion (if you have got here at all, bravo; if you have followed my rambling then 10 points to Gryffinpuff!).

Why I think this discussion is useful, at least for me, is that it gives me a way of thinking about different styles of gaming. Some approaches might emphasise the role of the player-world and the narrator-world, particularly the player-narrator. Others, may emphasise the Game-world and the character-narrator.

In my own running of games, I think I tend to the latter. I do not really use mechanics much, and often ask the players to narrate things from the characters' perspective. I might ask 'what does the lord look like?' That is a way, I think, of privileging the characters' and the game-world. This is not superior to other types of play, but it certainly suits my tastes.

I hope this has been an interesting read. I understand there is nothing revolutionary in this, but if it inspired any thoughts or counter-arguments, I'd love to hear them.

Next time, I'm either going to try and apply this same line of reasoning to a few more extracts from games, or I'm going to try and think about a definition of FKR based on the language people actually use.

(1) Discourse-world: The shared world in which communication happens. We are in one right now, even though it is spatially and temporally split.

(2) Text-world: I think game-world as a term works well as it puts emphasis on the "space of the fiction".(3) participant-accessible: I replaced participant with player and changed accessible to verifiable. I did the latter because I wanted to avoid thinking about who had the "right" to influence parts of a game.(4) enactor-accessible: enactors are anything that can influence things in a text-world, for us that is characters be they PCs or NPCs.(5) 'positioned within a participant-accessible text-world, when in fact they are experiencing an enactor-accessible modal-world' (Gavins, 2008, p.131). And you thought my blogpost was dense!

Comments

Post a Comment