Can we map where a thing is or its dimensions when playing RPGs? I'm not sure we can.

There's been a certain amount of discussion recently about the idea of conceptual mapping in RPGs, mostly inspired by the comments in this video on Video Game design.

The general idea is about applying a version of our understanding on how we form cognitive maps in our minds (imagine how you know the way to your nearest shop or back to your hometown). Taking that and applying it to designing levels in computer games. Raccoon Medicine has started an excellent series on thinking about the same ideas in terms of designing and running RPGs. I am not going to do the same because they are doing it better than I and you should head over and read them.

For this post, I looked at some actual plays (using the same as I used in this post on narrators) to see if I could identify evidence of this kind of mapping when players were moving characters. In short, I didn't really find it, and I am now not certain that this model of mapping necessarily applies to the imaginative space of RPGs (though I think it would to designing content for RPGs).

In this post I'm going to got through what I think the actual plays showed me and the close by considering what it means for running games.

Where things are doesn't really matter

Unlike video games and our own perceptual information, the imaginative space where RPGs exist is limitless and almost without rules. As a real human, I can say: 'I am on a chair at a table in a house, a town, a country'. As as an imaginative being I can say: 'I am beneath a chair, inside a table, around a town, before a country and, also, I am each of those things.'

What I found looking at the actual plays was that any kind of "map" of a traversable space for the characters was always secondary to their. For example:

- Sleepaway: "Look we gotta go, he would just grab your hand and start running back towards the kids."

- UVG (Troika): "You manage to guide the snail up the route".

- Dolmenwood (OSE): "I’m going to follow the footprints back to the cemetery. I’m not gonna enter it the cemetery. But I want to see if I can see disturbed graves skulls lying around with the teeth pulled out."

- 5e: "I'm gonna stealth back [and tell them what i've seen]."

- The Price of Coal: "He’s walking over to the Bailey residence."

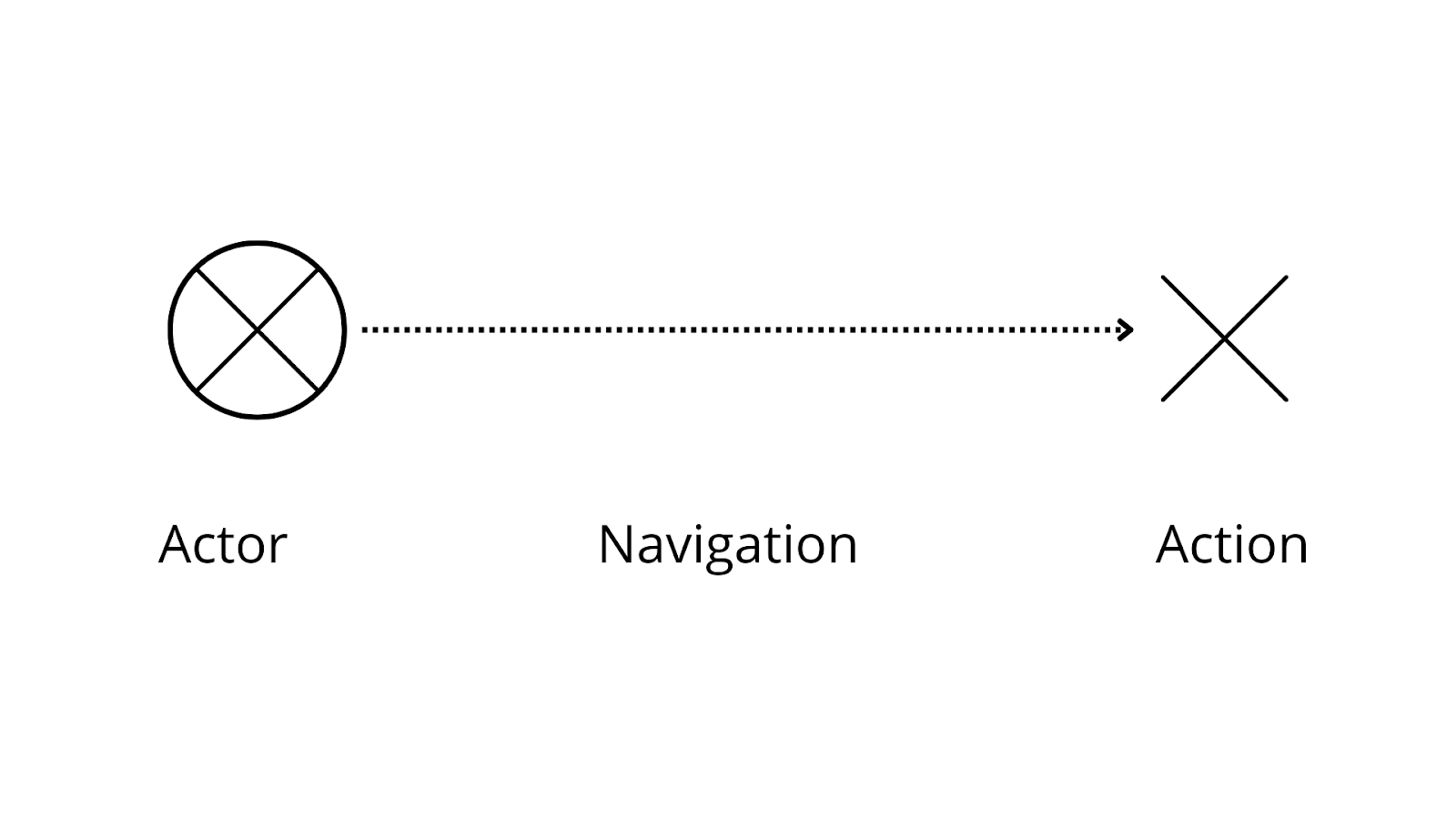

In these examples, the navigation (the movement of a character) just "happens" and it tends to happen to achieve some kind of action, even if it is just implied.

Example 1 from Sleepaway is particularly clear: the actual positions of the speaker and the kids isn't discussed at all but we assume they will be able to make it there. This is despite the fact that in "reality" that would require using landmarks, following paths and all of the other elements of conceptual mapping.

The actual nature of the navigation is almost immaterial. Take 'guide the snail up the route': that route could be winding spire of flesh (it is), or a billion light years of interdimensional chaos, or a small ramp. As long as we feel it is possible for that navigation to happen for the actor, the actual space of the movement is irrelevant.

Where things happen/ed matters.

My second point puts more emphasis onto the actions, and the objects that actions happened to. The actual plays focused on where actions might happen or where actions happened.

For example in this bit of navigation from Into the Odd, even though there is a mention of West/North etc., the recurring point of navigation is about where they came from.

- GM: 'you hear a kind of gurgling noise coming from the room you were just in with the water.'

- P1: 'I'm gonna place my lantern slightly more in the corridor in the west, from whence we came...'

- GM: 'you can hear almost what sounds like wet footsteps on the stone floor from that direction - from the lake that you came from.'

- P2: 'I'm gonna head toward the tunnel entrance where we hear this wet slapping coming from.'

In the first 3 of these we can see an object 'room with lake' or its corridor with actions associated with it, particularly their coming from it. In the final one a new object and action is emphasised: the tunnel and the sound 'we hear' at it.

This happens throughout the examples I looked at where an object (be that a person, building, or place) gained a solidity in the navigational map due to actions happening to it.

We might represent the example from Into the Odd as something like this, with the object being the tunnel/space they just came from and the actions associated with it below.

Where things can happen matters most.

So far I have suggested that in the imaginative space of the RPG that mapping is not about recalling actual locations but about the navigation towards actions, and the establishing of objects as parts of those actions. As part of this I am implying that positions and distances are almost non-existent.

However, obviously the relative position of objects matters. An example of this from the Dolmenwood game picks this out:

P1: 'I am sprinting, just dead sprint to the gate.'

P2: 'But Rag and Bones is Between you and the gate. '

- P1: 'Then I’m gonna try and run around him then. But I am just going for the gate, to get out the gate.'

In this exchange we see a bit of evidence for my first point. P1 actually doesn't care about the locations of objects, it is the navigation to the action (an implied "get to safety") that occupies him and when P2 picks out the challenge to this, the response is to say "whatever, I still try to achieve the action".

What P2 is pointing out though is the potential impossibility of P1's action due to the presence of another object.

I think this is what the relative positions of objects in the RPG world is about: the potential or impossibility of that action. In 5e game for example, combat happens, in which players talk about their distance from different things. What is clear in these cases is that what they actually talking about is there ability to take actions.

- 'Am I in [range]? - I'll get within 30 feet and fire...'

This then I think is the key point about what the conceptual map of an RPG space is. It is about the plotting and navigation of "potential space" - that is the metaphysical space that will allow for an action to take place. I think this corresponds even to the minutiae of distances.

Retunring to the Dolmenood encounter, as P1 begins to realise that he is not getting out of the situation unscathed, he asks:

- P1: 'If I grabbed her somewhere between the tower and the gravestones and it is somewhere on the path between myself and the gate. It’s not a super long distance is it?'

- GM: 'What's your encounter distance? 40 feet? I said it was 30 yards - so you can't make it this round.'

- P1: 'But where along the vector am I?'

- GM: 'Not quite halfway'.

The GM initially responds to pin things down to come to the conclusion of what action was (or in this case wasn't) possible: 'you can't make it this round'. Even the follow up is about the same with asking about the vector being something like 'how many actions will it take me to take the one action I want to'?

Objects then have an influence on each other, particularly when one leads to the impossibility of actions associated with other others. As Rag and Bones's arrival and its actions establish a change from vague discussions of difference to a plotting of relative space and the potential of navigation and action within that.

I'll try to plot a couple of these examples the first more simple from 5e. The second the complex demarcation of specific distances.

Why does this matter?

As always I've taken quite a theoretical approach to this issue, but this is because I don't think that RPGs are currently well described by models that come from other areas. Therefore, I want to try and play with the language and concepts of RPGs in a way to encourage new thoughts.

In this case though, I think there are a few practical takeaways:

- Don't stress about absolute positions - they might not really exist.

- Discuss absolute positions in terms of actions.

- "The tower is a short walk beyond the castle, you can see a flag fluttering on its top."

- Discuss the potential/impossibility of actions rather than dimensions and distances. "The creatures burst in, they look just on the range of your bows".

- Think about the players' map as the history of objects they have interacted with.

A concluding thought

Building on point 4 above, I wonder if the conceptual map of an RPG looks very linear, and is probably totally temporal. It might be a path in which the "I" of the characters, move from action-object to action-object. Here is a very simplified version of what that map might look like for one of the players from the Dolmenwood game.

This brings us back to our original starting point and some of the same terms coved in the YouTube video starting this post: if the map is a path, perhaps there are also nodes where multiple strings of actions started (such as the 'gate' in the example here), or landmarks which represent objects of multiple or significant actions (such as the tower).

Thanks for reading, if you have any counter-points or comments I'd love to see them. Next, I think I'm going to be writing up next some thoughts about designing an explicitly FKR game.

Comments

Post a Comment